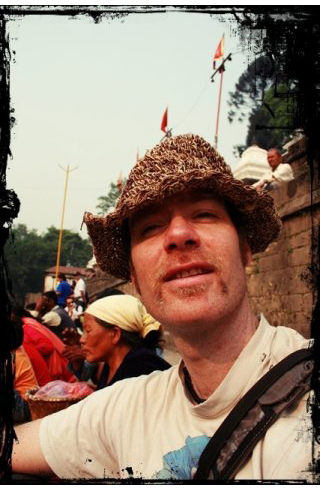

John Wall Barger is a Halifax-based poet. (See Voice review of his recently published Pain-Proof Men.) Recently John took the time to talk to Wanda Waterman St. Louis (who, along with Bob Snider, shares the same home town with John) about poetry and the poet’s life.

John Wall Barger is a Halifax-based poet. (See Voice review of his recently published Pain-Proof Men.) Recently John took the time to talk to Wanda Waterman St. Louis (who, along with Bob Snider, shares the same home town with John) about poetry and the poet’s life.

Tell me what your life was like while you were living in Bear River.

It was 1975, I was five, and we’d just moved from southern California to a forest in Canada. First we lived in a tipi my mother stitched. I remember thinking it was odd that ferns were growing in the living room. My dad built a cabin out of an old house he helped tear down. I liked it in Bear River. I climbed and fell out of a lot of trees, and the deep eerie silence of those woods stuck with me. My poem ?Doberman? describes what it was like to be attacked by a local dog. I think I was always a city kid. After a year, we moved to Manhattan, and I was ecstatic.

When did you first think you could write poetry?

I wrote my first poem when I was 17, and liked the feeling. It was a kind of power that nobody else had any say in. So I began writing a lot of poems. Quick, sans revisions. I definitely thought I could write poetry. Ginsberg and Kerouac and Bukowski were models, but I kept drifting toward the mythic and surreal. Later Blake blew my mind. The first time I wrote one that I can bear to reread was about 10 years after. Still now, when a poem bears weight, It’s a lovely surprise.

How does it feel to write a poem? From start to finish?

If I’m not writing consistently, I feel kind of ill, psychically. On a jag, the mind goes mercury. Fluid, open, flexible. Although writing is obsessive, it somehow contains the antidote to fear and worry. Starting a poem is terrific. It’s the stage I love the most: ransacking the toy-box of archetypes. I revise compulsively, but I’m less exuberant about the niggling latter stages. At a certain point, when a poem seems to be getting close, I would love to hand it over to someone at H&R Block, and have them bottom-line it for me. I don’t ever feel quite finished with any poem.

How do you hone your art?

How do you hone your art?

Reading. I ape everything I like. Lately It’s been James Tate, D.A. Powell, Pasolini, and Kay Ryan. I unlock my jaw like a snake and swallow their work. For a while, when I fall in love with a new writer, I write poems that are so derivative and plagiarized that they must be thrown away. But now and then I can adopt some aspect, some twitch, of what they do as my own. Some writers, like Kay Ryan, are so singular, or at least distinct from me, that I can learn nothing but only admire from afar.

What conditions do you need in order to be as creative as you need to be?

I have fabricated a life that, more or less, allows me the time and energy to support my work. This has involved a lot of luck, and the generosity of the people around me, for which I am very thankful. I work as a part time prof?just enough to keep my hapless left brain firing, like fireworks in fog?but not so much that it impedes writing time. The odd grant is invaluable. Travelling helps fill the reservoir. Friends swim in the reservoir.

What role do you think poets play in modern culture? What role should they play?

I like that Charles Olson used to advise Roosevelt. Trudeau had ?meetings? with Marshall McLuhan, who, with his Zen koan-like ?probes,? was a kind of media poet. But what on earth did Roosevelt or Trudeau learn from these lovely lunatics? I’m not interested in poetry that teaches me lessons about culture. That kind of art (rare exceptions come to mind, like Neruda and Jenny Holzer) makes me feel deceived. Can the deep mysteries really be condensed into stereotypes and aphorisms?

The poets I admire don’t judge. They watch, and report. They speak out of the dream. The environment is going to hell, of course, but I don’t think It’s the job of poets to critique this, at least in a literal way. Perhaps poets today are useful because they (usually) do not look at the world through the ubiquitous commercial lens. This job might be enough, for our fragile poets.

How did you first get the idea for the title Pain-Proof Men?

I’ve been obsessed for years with carnival culture, and at one point I wanted my first book to be all about circuses. A pain-proof man is, of course, a performer in a sideshow who stabs himself with pins and needles, as a little mob looks on. I liked this as a metaphor for the artist. Most of the circus poems fell away from the manuscript, and the idea expanded to pain in general. I don’t think suffering is just ours. We all know its texture, its smell. So It’s a potential point of connection with others. Heartbreak, in balance, leads to empathy.

Do you have any plans for the immediate future? The distant future?

My lifestyle now is the best one I’ve been able to think up. I live in Halifax, Nova Scotia, though It’s now June and I haven’t been there yet this year. I’ve been working on a translation of the Italian poet Pasolini, so next winter, like the last, I’ll live for a few months in Italy. I try to live well each day, and not worry about the distant future.