From March 11th to 13th, the History Department of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign sponsored the “Fifth Annual Graduate Symposium on Women’s and Gender History.” Established in 1867, and located about three hours south of Chicago, UIUC has over 38,000 students, and boasts the world’s largest public university library collection.

From March 11th to 13th, the History Department of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign sponsored the “Fifth Annual Graduate Symposium on Women’s and Gender History.” Established in 1867, and located about three hours south of Chicago, UIUC has over 38,000 students, and boasts the world’s largest public university library collection.

When my wife was invited to present a paper at the UIUC history symposium, I also decided to attend the conference, intrigued by the prospect of seeing a part of the U.S. that would be completely new to me. It was a fascinating experience. In particular, the legacy of racism was demonstrated to me in some very tangible and occasionally disturbing ways during our brief trip.

I didn’t have to leave Canada to witness racism’s legacy, however. At Toronto’s Pearson International Airport, I noticed the shoeshine stands where white businessmen sat on elevated chairs, having their shoes polished by black attendants. Though very much in the public’s view, this practice, reflecting long-standing race and class divisions rooted in the history of slavery, strangely did not appear to a receive a second glance from any of the countless travellers passing through the busy terminal. The implications of this scene actually made me feel uncomfortable.

Later that day, after landing at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, I again encountered shoeshine stands, reflecting the same racial division that I had witnessed in Toronto. Around the airport, the racial divide was rather glaring: while whites were employed in a range of occupations, black workers appeared to be restricted to menial tasks.

From O’Hare, we travelled by Bluebird Express & Charter Inc. through Chicago and across the Illinois prairie to Urbana. The friendly bus driver was anxious to share his observations about Illinois with his two passengers. He started with Chicago’s highlights, including a neighbourhood where one can sometimes see Oprah Winfrey.

From O’Hare, we travelled by Bluebird Express & Charter Inc. through Chicago and across the Illinois prairie to Urbana. The friendly bus driver was anxious to share his observations about Illinois with his two passengers. He started with Chicago’s highlights, including a neighbourhood where one can sometimes see Oprah Winfrey.

“For a while the Japanese owned it” he said, as he pointed out the Sears Tower on our way of Chicago. “But we got it back” he announced triumphantly, before heading through Al Capone’s old haunts.

He continued to talk as he drove on, past the black soil of Illinois’ farmland that here and there sported an occasional green field of winter wheat. He was curious about the reason for our visit to Urbana, and was quite excited to learn that we would be attending a history conference.

“History! Oh, I wish you had told me sooner!” And with that, he reached for his wallet, and pulled out a card bearing his name and a flag with horizontal stripes and a ring of stars: “Do you know what kind of flag that is?”

After we failed to produce the right answer, he proudly informed us that it was a Confederate flag, although different from the Confederate battle flag that we were used to seeing. Our driver explained that only a few years ago, he had discovered that one of his ancestors had been a distinguished soldier who had fought on the side of the Southern States. I wondered if he would have been so proud of the Confederate flag if he were a non-white.

I asked if any important American Civil War battles were fought in Illinois. That was not the case, he indicated, but then added that some of the Indian Wars had been fought in the state. When asked if Native Americans were much of a presence in Illinois, the driver responded that there were really none around. He didn’t elaborate.

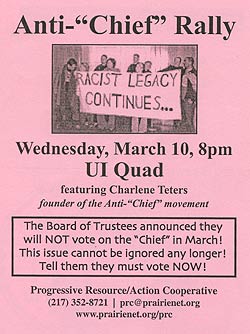

After checking into the Urbana Travelodge, my wife and I decided that the best way to get to know the city was to go for a walk. After about 20 minutes, we reached the university campus. There, we strolled into the middle of a protest against the UIUC school mascot. The image of “Chief Illiniwek”, we soon learned, is used by the university’s sports teams, and a Caucasian dressed as a Native American appears at sporting events performing a mock Native dance.

After checking into the Urbana Travelodge, my wife and I decided that the best way to get to know the city was to go for a walk. After about 20 minutes, we reached the university campus. There, we strolled into the middle of a protest against the UIUC school mascot. The image of “Chief Illiniwek”, we soon learned, is used by the university’s sports teams, and a Caucasian dressed as a Native American appears at sporting events performing a mock Native dance.

Although a cold wind was blowing through the quad, hundreds of students and concerned citizens, representing various racial backgrounds, had gathered to protest the stereotyping of Native Americans, their history of mistreatment, and the exploitation of their culture. In the midst of Urbana-Champaign’s dignified campus, students and the larger community were confronting racial stereotyping head-on. A news crew from a local television station was there too.

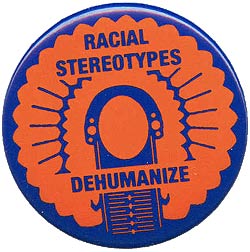

Native speakers described experiences in boarding schools that closely paralleled Canada’s history of residential schools. There were speeches from representatives of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and a South Asian Students group. A student handed me a button that warned “Racial Stereotypes Dehumanize”, saying that she thought it was “cool” that a pair of Canadians was participating in a protest against “The Chief.”

The organizers led the crowd in chanting, “Every race, colour, creed, we want the Chief to go with speed!”

Earlier that day, the bus driver had implied that there were no “Indians” left in Illinois, but the demonstration seemed to challenge that notion. In fact, the Indians that were invisible to the driver were not only evident in the protest on campus, but also appeared later that night on the news, and again in the next day’s newspaper.

The next morning, I read the newspaper account of the protest in the reception area of the motel. The newspaper also carried a column supporting the use of “The Chief.”

Apparently, those who wanted to retain the mascot projected a real persona upon this fictitious aboriginal, and asked others to also “honor the Chief.”

Apparently, those who wanted to retain the mascot projected a real persona upon this fictitious aboriginal, and asked others to also “honor the Chief.”

After breakfast, my wife and I continued my exploration of Urbana-Champaign’s streets, stores, and bookshops. We noticed outlets selling University of Illinois apparel. Prominent among the articles for sale were those that featured “The Chief.” Evidently, the sale of licensed merchandise provided some motivation for keeping the controversial mascot.

The controversy over “The Chief”, and the associated colonialist implications, made the university’s history symposium seem especially relevant. Three days later, nevertheless, the conference was over, but I had learned much in that period.

The symposium had taken place in a very supportive academic environment, and I had met many gifted young scholars. I was thoroughly impressed by the calibre of the presenters, and the knowledge of the commentators who spoke at the UIUC Graduate Symposium on Women’s and Gender History.

The symposium had taken place in a very supportive academic environment, and I had met many gifted young scholars. I was thoroughly impressed by the calibre of the presenters, and the knowledge of the commentators who spoke at the UIUC Graduate Symposium on Women’s and Gender History.

Although our visit to Urbana was short, I enjoyed my time there. Still, it left me with much to think about, especially the issue of racism. No doubt we are all surrounded by racism, but it becomes easier to recognize when we are outside of our “normal” contexts. But racism still had a particular resonance for us back home in Edmonton.

A couple of days after our return, a headline in the Edmonton Journal reported, “‘Mohawks’ in Manitoba school aren’t aboriginals – real natives want change” (March 18, 2004, p. A3). It dealt with the Morden Collegiate Mohawks sports teams, which have been criticized for using aboriginal symbols. The story echoed concerns that were voiced in Urbana over “The Chief” and even referred to our own Edmonton Eskimos’ controversial moniker.

Whether we live in Urbana or Edmonton, we live with issues of race and history.

A Sit-In Against “The Chief”

Although I witnessed a demonstration against “The Chief” in March, efforts to do away with the controversial mascot go back 15 years. In the past, anti-“Chief” activists have accused the university board of simply avoiding the issue. When the April 15th University of Illinois Board of Trustees meeting at the Chicago campus was cancelled, The Progressive Resource/Action Cooperative (PRC) suggested that the cancellation was to allow the Board to avert a resolution meant to eliminate “Chief Illiniwek.”

To pressure the U of I Board to deal with the “Chief Illiniwek” resolution, a coalition of UIUC students, alumni, faculty, members of the community, and Native representatives occupied the Swanlund Administration Building on the UrbanaChampaign campus. Protestors demanded the immediate elimination of the “Chief Illiniwek” symbol from the University. They also demanded that a formal apology be made to Native Americans for the hurt caused by the use of the school mascot. In addition, they wanted assurances of increased and more secure funding for the Native American, and other minority and cultural studies programs for the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign.

Authorities restricted access to the Swanlund Admin Building, and cut off food supplies in an attempt to force demonstrators out. The attempt failed: before the police had arrived protesters had already amassed a large supply of food.

Demonstrators received supportive emails throughout the sit-in, and several major newspapers in the U.S. covered their protest. In Britain it was reported in The Guardian.

The sit-in ended on April 16th, after more than 32 hours, when demonstrators reached an agreement with U of I Chancellor Nancy Cantor and Trustee Frances Carroll. Although the university representatives did not agree to the elimination of “Chief Illiniwek,” demonstrators were promised that the anti “Chief” resolution would be on the agenda of the Trustees’ meeting scheduled for Thursday, June 17th in Chicago. Furthermore, sitin participants were guaranteed that there would be no disciplinary action against them.

The Progressive Resource/Action Cooperative:

http://www.prairienet.org/prc

prc@prairienet.org

Retire The Chief:

http://www.RetireTheChief.org

The Graduate Symposium on Women’s and Gender History

During the Graduate Symposium on Women’s and Gender History, talented and knowledgeable men and women pursuing their masters or doctoral degrees presented a broad range of interesting and innovative papers.

During the Graduate Symposium on Women’s and Gender History, talented and knowledgeable men and women pursuing their masters or doctoral degrees presented a broad range of interesting and innovative papers.

It is impossible to do justice to the depth and range of topics that were covered in the symposium, but a small sample is presented here.

One presentation was concerned with the history of American college football, and another dealt with animal-to-human implants to improve male libido. A comparison of Nazi and US eugenics programs revealed that in some cases they were actually quite similar, although the US program continued after the Nazis were defeated. A paper concerning the Canadian Girl Guides placed that organization within an anti-communist framework: following the Russian Revolution, there were concerns throughout the British Empire that girls from slums would become Bolsheviks unless they were instilled with the discipline and training that membership in the Girl Guides would provide. Another student presented an evaluation of East and West German cookbooks, examining the ways by which opposing ideologies were represented in Cold War kitchens.

Looking at a different domestic front, one young scholar examined the changing role of women in Italy’s Mafia. There was also a lecture on zoot suits that delved into the issues of clothing and perceived threats to masculinity. In 1943 riots broke out in opposition to poor young Mexican-American men wearing the oversized jackets and large baggy pants typical of zoot suits. U.S. servicemen stripped the zoot suit-attired Mexican-Americans, and tried to destroy the offending clothing. Race, class, and gender converged as the lecturer shed light on this almost forgotten Los Angeles race riot.

The symposium offered a very supportive and inclusive atmosphere. The participants, drawn from across North America and as far away as Europe, were friendly and anxious to learn about the work that their colleagues were pursuing. The students and faculty of the University of Illinois did an admirable job of hosting the symposium.

There was also a round table discussion on “Crossing Boundaries.” During this session, we learned that some university history programs were making connections with the wider community. Graduate students gave lectures at their local high schools, for example, in an effort to encouraging grade-school students to become interested in historical issues.

It was clear that the general public, and elected officials in particular, needed to be educated about the importance of history programs, and the need to provide proper funding for university history departments.

Website for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Graduate Symposium on Women’s and Gender History: http://www.history.uiuc.edu/wghs/