It is popularly assumed that Marie Antoinette lived a life of extravagance while French peasants starved, and that for this she was beheaded, so a film retelling her story requires a new angle. Enter writer and director Sofia Coppola who provides us with a Marie Antoinette (Kirsten Dunst) reminiscent of an innocent Lady Diana Spencer overwhelmed by her new role in a marriage devoid of passion. Later, this same character becomes something of a hedonistic Paris Hilton drowning in excess.

It is popularly assumed that Marie Antoinette lived a life of extravagance while French peasants starved, and that for this she was beheaded, so a film retelling her story requires a new angle. Enter writer and director Sofia Coppola who provides us with a Marie Antoinette (Kirsten Dunst) reminiscent of an innocent Lady Diana Spencer overwhelmed by her new role in a marriage devoid of passion. Later, this same character becomes something of a hedonistic Paris Hilton drowning in excess.

Though Coppola portrays the 18th century French court in period costume with Versailles as the setting, the atmosphere is very modern, with a sound track featuring rock music (including cuts from Bow Wow Wow, Siouxsie & The Banshees, Adam & The Ants, and The Strokes). This version of the French Queen’s biography may not always be historically accurate, but it does breathe new life into a familiar story. Unfortunately, the overall effect portrays barefaced materialism as a virtue, with the spendthrift Queen as its martyr.

In this film, based on Antonia Fraser’s recently reprinted and repackaged book, Marie Antoinette: The Journey, we see events unfold from Marie Antoinette’s perspective. As the teenage daughter of Maria Theresa, Empress of Austria, Marie Antoinette is thrust into the French court of Louis the XV. She is sent to marry the Dauphin, a young man whom she has never met before. The marriage is meant to seal an alliance between France and the Hapsburg Empire.

Marie Antoinette’s new husband, the future Louis XVI, seems to have no passion for his bride. Instead, the Dauphin is preoccupied with hunting and lock making. (His choice of hobbies and his lack of interest in sex could be the basis for an interesting Freudian analysis).

Eventually, all sorts of pressures are brought to bear on the new bride, as she is blamed for the couple’s failure to produce an heir. While some members of the court dismiss her as a cold Austrian, her mother writes Marie Antoinette that she must summon all of her feminine charms to consummate the marriage, produce an heir, and solidify the alliance. Yet, for all of Marie Antoinette’s efforts and her own sexual desires, she cannot ignite any passion in her young husband.

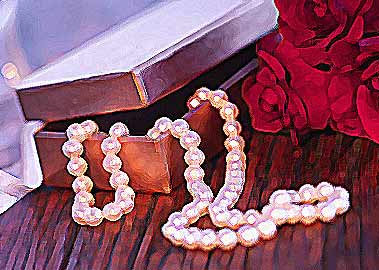

Out of frustration, she lavishes all kinds of extravagances upon herself. She distracts herself with wild parties and merrymaking, and buys the finest, most expensive clothes and jewellery. In short, the sexually frustrated wife becomes a party girl and shopaholic. With Bow Wow Wow’s “I want Candy” as musical accompaniment, she and her clique set out on a shopping frenzy. These images of youth, privilege, fashion, celebrity, and excess seem to have been torn from the latest issue of People magazine.

Fashion and jewels are not her only diversions. Marie Antoinette also has a little hobby farm, complete with livestock, herb garden, and chalet built for herself, like a Neo-classical Paris Hilton dabbling in “the simple life”. Marie Antoinette also takes a lover, as if her other pursuits do not provide enough distraction. In reality, nevertheless, it is not certain that she ever had an affair with Axel Fersen, the Swedish Count depicted in the film (Hohenadel, October 20, 2006).

Nor is the queen the only distracted individual in the court. Throughout the film, there are hints that France’s military is overextended, its citizens overtaxed, and the peasantry starving, but the ineffectual Louis and his circle are completely detached from everyday life outside of their enclave. To some degree, we can understand their shock when they learn that the Bastille prison has been stormed, and a mob of angry peasants surrounds the palace. Presented only from Marie Antoinette’s point of view, however, we are given little context for understanding the people’s anger.

The audience is not shown Marie Antoinette’s beheading, or for that matter any of the revolution’s bloody executions. Instead, in the next to final scene, we see the royal family taken away by coach. The implication is that Marie Antoinette nobly accepts the fate that awaits her. Never mind that in reality the family made a failed attempt to escape to Austria, only to be recaptured, but that would tarnish Coppola’s vision of the French Queen as a submissive sheep led to slaughter.

To her credit, Coppola deftly conveys sexual liaisons, as well as the revolution’s impending violence, without resorting to gratuitous images. (The film has been given a PG rating).

In fact, Coppola presents us with a film that is simply beautiful to watch. From the palace interiors and its gardens (filmed on location at the Chateau de Versailles), to the silk and lace, from shimmering jewels to the buttoned shoes, the screen is flush with bright and colourful eye candy. It is a visually stunning movie experience.

It is also a sympathetic portrayal of Marie Antoinette, and a re-examination of her life is certainly overdue. Unquestionably, her persona has been overlaid with myth. Her contemporary enemies spread slanderous stories of her supposed sexual excesses. She was despized as a foreigner. Ultimately, she was demonized by the French Revolution. Perhaps there is something to Coppola’s take on the unfortunate Queen, although there is the lingering sense that the portrait is something of a whitewash.

Even if everything in the film is not completely factual, Kirsten Dunst makes the story believable. She is entirely credible as a giggling teenager, frustrated wife, seductress, and besieged sovereign. She deserves much of the credit for making Coppola’s revisionist depiction succeed.

Coppola, however, is not alone in wanting to rehabilitate the maligned sovereign’s image. Members of France’s Marie Antoinette Association, concerned about the reputation of the long-dead Queen, are unhappy with the sexuality portrayed in the film (even though the film contains no nudity and depictions of sexual acts are more suggestive than revealing). These rather sensitive modern-day supporters of Marie Antoinette are particularly distressed that Marie Antoinette is represented, in their view, as a “libertine.” (Oddly, the portrayal of the Queen spending extravagantly while peasants starve does not appear to bother the Marie Antoinette Association).

Actress Kirsten Dunst, in response, acknowledges that the film may not always be faithful to history and provides a rather concise appraisal of the film. “It’s kind of like a history of feelings rather than a history of facts. So don’t expect a masterpiece theatre, educational Marie Antoinette biopic.” (World Entertainment News Network, October 2, 2006)). More than anything, it is a seductive film, beckoning the viewer to uncritically accept its message about the beauty of materialism. The protagonist’s consumerism, fueled by an overriding sense of entitlement, due to her station in life, and a marriage without passion, is depicted as being sexy and exhilarating.

Furthermore, the screenplay manipulates Marie Antoinette’s biography in such a way as to remove it from its historical context. Presented completely from Marie Antoinette’s perspective, the audience is never shown the effect of the Queen’s decadent lifestyle upon the rest of the nation, who riot because there is a shortage of bread. We are never given the chance to sympathize with the peasantry, simply because we do not see them. And when, near the end of the film, the masses finally make a fleeting appearance, they are merely unruly party-crashers putting a damper on the royal frivolities. Not surprisingly, the revolution’s grievances (reasonable or not) are never truly articulated in this terribly unbalanced treatment of a story based — to some degree or another — on reality.

As a result, Coppola’s film almost seems to exalt Marie Antoinette’s maniacal consumerism (which is not to overlook the King’s role in the royal finances) even though the Queen’s excesses come at the expense of the peasantry. In spite of this, she is depicted as an innocent and misunderstood rich girl, perhaps even something of a martyr as she heroically stands by her husband’s side rather than fleeing, prostrates herself before the French peasantry, and then compliantly allows herself to be taken by carriage to Paris where she will (eventually) meet her fate.

This alluring portrait of Marie Antoinette appears to be responsible for much of the film’s success. In a New York Times article, Eric Konigsberg credits much of the film’s popularity, in North America at least, to a lack of knowledge about history, but also to many North Americans’ hopes (however slim) that they too could attain such a decadent lifestyle (Edmonton Journal, October 29, 2006)). Indeed, this film and public reaction to it may reveal more about our society, than it does about history.

Coppola’s Marie Antoinette is a fascinating, yet troubling film experience. It is, first of all, a gorgeous movie, offering a novel and enticing spin on an historical biography. At the same time, it celebrates frenzied materialism, regardless of the consequences that this behaviour might produce for other individuals. As if that were not problematic enough, the film’s most decadent and self-serving character is regarded as an innocent martyr. All things considered, this movie seems to be the celluloid equivalent of fast food. It is tasty and easy to swallow, but it is ultimately bad for one’s digestion.

References

Coppola, S. (2006). Marie Antoinette [motion picture]. Sony Pictures Entertainment.

Edmonton Journal staff (2006, October 29). Made over into a thoroughly modern Marie. Edmonton Journal: D2.

Fraser, A. (2001). Marie Antoinette: The Journey. Nan A. Talese.

Hohenadel, K. (2006, October 20). French royalty as seen by Hollywood royalty: Coppola focuses on emotional life of maligned French queen. New York Times News Service. Edmonton Journal: G3.

World Entertainment News Network (2006, October 2). “Historians Blast Dunst’s Marie Antoinette.” http://www.teenhollywood.com/d.asp?r=133548&c=1014.