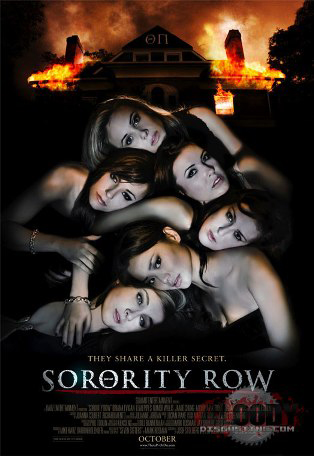

When I was younger, I was very much drawn to classic slasher-horror films, such as the Friday the 13, Hallowe’en, and Nightmare on Elm Street franchises. The reasons for this, I guess, were pretty typical. For one thing, it was escapist entertainment for a troubled, angst-ridden teen; after all, my life may have felt pretty bleak and overwhelming at the time, but it was not quite as bad as having one’s head split open by an axe-wielding maniac, or being ripped to shreds by razor-sharp claws. For another thing, the tension and catharsis being experienced while sitting in the darkened movie theatre, eating popcorn beside my friends, was a communal event. We were cringing together, holding our breath together, shrinking into our seats together, jumping in fright together, laughing together, displaying mock bravado and nonchalance together. For an eccentric and essentially introverted kid who often felt isolated and out-of-step with peers, it was good to feel in this way connected, at least temporarily, to others. (I also remember feeling the same way—free and alone, yet part of some communal happening—out on nightclub dance floors, the subsonic bass vibrating in my chest bone, surrounded by others who were similarly being transported by the music.) As well, the violence in these gory b-movies was gloriously excessive, and lavishly cathartic – almost operatic. In a world that often felt numbing, monotonous, and bleak, it was like a sweet burst of adrenaline, as opposed to a steady drip of novocaine. Finally (and I had no awareness of this at the time, but all the same I have come to realize this last point is the most significant to me) witnessing atrocities faked in the name of art somehow made me feel better about the world. Far from making me afraid or depressed, seeing these horror films somehow comforted me.

When I was younger, I was very much drawn to classic slasher-horror films, such as the Friday the 13, Hallowe’en, and Nightmare on Elm Street franchises. The reasons for this, I guess, were pretty typical. For one thing, it was escapist entertainment for a troubled, angst-ridden teen; after all, my life may have felt pretty bleak and overwhelming at the time, but it was not quite as bad as having one’s head split open by an axe-wielding maniac, or being ripped to shreds by razor-sharp claws. For another thing, the tension and catharsis being experienced while sitting in the darkened movie theatre, eating popcorn beside my friends, was a communal event. We were cringing together, holding our breath together, shrinking into our seats together, jumping in fright together, laughing together, displaying mock bravado and nonchalance together. For an eccentric and essentially introverted kid who often felt isolated and out-of-step with peers, it was good to feel in this way connected, at least temporarily, to others. (I also remember feeling the same way—free and alone, yet part of some communal happening—out on nightclub dance floors, the subsonic bass vibrating in my chest bone, surrounded by others who were similarly being transported by the music.) As well, the violence in these gory b-movies was gloriously excessive, and lavishly cathartic – almost operatic. In a world that often felt numbing, monotonous, and bleak, it was like a sweet burst of adrenaline, as opposed to a steady drip of novocaine. Finally (and I had no awareness of this at the time, but all the same I have come to realize this last point is the most significant to me) witnessing atrocities faked in the name of art somehow made me feel better about the world. Far from making me afraid or depressed, seeing these horror films somehow comforted me.

I think I understand now why this is so. From a very young age I had been a pretty creative child, forever drawing, making up stories, playing games of make-believe. In my experience, there are few things in this life that are not a double-edged sword, and the price to be paid for having imagination is fear. And, of course, being immersed in the existential human condition means there is never any shortage of things to be afraid of. As a young child, those fears took the shape of ghosts, shadows, the dark, parental violence. As a teenager, they visited me in the forms of loneliness, sexual confusion, and the inky blackness of the cold war nuclear shadow.

But, if imagination was the venom, it was also the antidote. Imagination, in the form of art, was a means of exploring fear in a satisfying and transformative way. Like a good blues song, those old horror films refused to turn away from the troubles of life. Instead, they confronted them on their own terms – in the domain of fantasy. In doing so, they managed to perform a sort of alchemy, transmuting anxieties into some psychological substance that seemed vital, exciting, and strangely beautiful.

Over the years, my tastes have broadened. I’m still fond of Wes Craven, but overall I prefer to get my dosage of dark aesthetic vibes and angst-filled dystopian visions from the films of Kubrick, Bergman, and Fincher, from the novels of Martin Amis, Chuck Pahlaniuk, and Margaret Atwood, from the music of Tom Waits, Portishead, and Nick Cave. I will always have an appreciation for all those old slasher flicks, though, and the part they played in helping me through some shitty years.