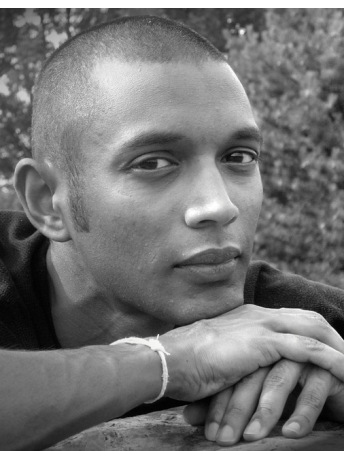

Dinuk Wijeratne is a prolific composer, a brilliant pianist, and a musical visionary with an aesthetic informed by the Buddhist principle of balance. With a sensibility honed by one of the best musical educations?both academic and autodidactic?imaginable, and, still in the midst of a continent-spanning performing career, Wijeratne welcomes the quiet of his newfound home in Nova Scotia for the opportunity it affords him to focus on composition and his duties as director of the Nova Scotia Youth Orchestra.

Dinuk Wijeratne is a prolific composer, a brilliant pianist, and a musical visionary with an aesthetic informed by the Buddhist principle of balance. With a sensibility honed by one of the best musical educations?both academic and autodidactic?imaginable, and, still in the midst of a continent-spanning performing career, Wijeratne welcomes the quiet of his newfound home in Nova Scotia for the opportunity it affords him to focus on composition and his duties as director of the Nova Scotia Youth Orchestra.

Complex Stories, Simple Sounds, his CD collaboration with clarinetist Kinan Azmeh, is soon to be reviewed here in The Voice. He recently took the time to talk with Wanda Waterman St. Louis about Robert Altman, concept-driven composition, and the importance of music in education.

Nova Scotia as Artist’s Terroir

I really enjoy Nova Scotia for the easy access to tremendous natural beauty (the lake near my home is a daily visit spot in the summer and fall). There’s a calm and solitude that is really conducive to creative work; you can work in relative isolation and get deeper into your work. Then there are the personal qualities of the people here?warmth, an easygoing nature, and a lack of pretension?that I hope will never change.

Lessons from a Renegade

My favourite film director is Robert Altman. His attitude was always that he would just do a project if it interested him even if he had to give studios the runaround (which he did with M*A*S*H*). He was a real rebel who ultimately had a lot of compassion for actors and for his work, and he would use or avoid the studio system to suit his own interests. He suffered for it, yes, but he created great work.

I read a lot about his method of directing because directing films and conducting orchestras are very much analogous. Because I’m a performer and also a leader, i.e., a ?director,? I have to figure out the differences between all of those things. For instance, when You’re creating you have to have something in mind regarding the practicalities of how It’s going to be performed. But once a work is created you have to summon a kind of leadership and then work with your actors to bring it to life.

Kevin Spacey said the genius of Altman was that he allowed actors to think that they had more freedom than they actually had, which I think is fabulous. Altman probably got something even better than he wanted because he had the flexibility to listen to actors? suggestions.

Kevin Spacey said the genius of Altman was that he allowed actors to think that they had more freedom than they actually had, which I think is fabulous. Altman probably got something even better than he wanted because he had the flexibility to listen to actors? suggestions.

That’s the kind of leadership I aspire to. But It’s actually much harder in the classical music industry than it is in film because we’re working with a text with less of a margin for freedom. I have to say I find this a frustrating aspect of working in the classical genre as opposed to a genre that involves improvisation.

All of a Piece

The biggest cultural influence on my music has been Indian classical music, and It’s not, to be honest, the melodic influence so much as the rhythmic influence. My melodic influence is a mainly modal language that comes from modern Western classical music and from some world music. My rhythmic language comes from north Indian music, particularly the sounds of the tabla, which have hugely changed my language.

And then there’s the whole Middle Eastern thing that I got into because of Kinan Azmeh. I’m not really much of an expert on any of that but aurally I know the style. But when we work together we’re not trying to create something traditional at all, whereas my approach to the Indian influences are much more rigorous because I know a lot more about the actual workings of those genres.

I love combining musical influences. I’m basically an eclectic in every way. I was taught by eclectics and I only seem to work with eclectics. But I never do synthesis for its own sake. I never think consciously, ?this needs to be mixed with that.? Ultimately everything is concept-driven, so if I think something needs a certain element for the sake of the concept and just because I’m moved by it then I’ll use it.

Working from a Concept

The fun part for me is the concept stage, when I get to plan what happens in the piece. My attitude toward what I create is that everything must have a unity about it. If you want to achieve something very Mozartian you have to trim the fat and you can only do that with a clear vision.

Educating the Whole Person

Daniel Barenboim is my favourite musical philosopher and his big credo is that music is a metaphor for life. I believe absolutely in that; music is the perfect tool for understanding yourself and the world, not in terms of specific events but in terms of how human beings function in society and in themselves. It’s escapism and also a window to understanding. People can reach this understanding even if they don’t play an instrument.

Counterpoint, for example, is a means of presenting an opposing argument that can freely express itself and still be harmonious. If you listen to even a very simple Bach piece that has just two lines, the two lines are expressing themselves without compromise. That’s just one of many examples in music.

There is no other discipline that so thoroughly combines every aspect of being human than that of physically playing an instrument. You’re combining the physical, the emotional, the intellectual, and the spiritual. But educators need to understand that music is so much more than a fun, extracurricular thing. It is fun but they need to know what else music can offer, which is just as important as mathematics or any other subject.