Community-Based Management Versus Backroom Deals

Community-Based Management Versus Backroom Deals

This is the first in a two-part series on the growing privatization of the clam industry in southwest Nova Scotia.

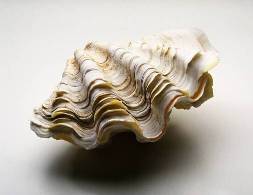

If you’ve driven along the Fundy shores of southwestern Nova Scotia at low tide you may have seen a solitary figure or two lurking at the outer edge of a mud flat, stooping enigmatically over small patches of ground. These people are digging up the little bivalve molluscs that have come to form an indispensable part of the world’s dinner menu. Accomplished by using a bucket and a hack (a sawed-off pitchfork with tines bent perpendicular to the handle), clam harvesting is one of the most cost-effective and environmentally safe ways of making or supplementing a year-round living off the sea.

Clams must be harvested at low tide, which happens twice a day and lasts for only a couple of hours. The clammer searches for holes in the mud and starts digging. Anything smaller than an inch and a half has to be put back into the hole to be allowed to grow to maturity.

Self-employed clammers take the clams home for shucking (shelling and beheading, pronounced SHAW-king) and sale to a licensed clam buyer. Clammers who dig on closed beaches for Innovative Fishery Products (IFP), a local company that buys and processes local clams for export and has become the employer of nearly every clam digger in Digby and Annapolis counties, have only to dig; the IFP truck drives to the beaches where its clammers are digging and loads the clams onto the truck directly from the beach. These clams are taken to the plant for depuration and shucking before being shipped to the buyer.

In the days before IFP’s rise to power clam diggers were an independent lot. A hard worker could support a family and still have time to raise it properly. A digger was not at the mercy of fickle job markets and bosses. Digging required minimal formal education and only the most basic of tools. But since IFP has effectively cornered the market for clams, more and more clam diggers are finding themselves forced to work for the company, and the life just isn’t what it used to be. The absence of benefits wasn’t such a trial when clamming could generate a living wage, but now that diggers are being paid less for clams that are becoming harder to find some of them are wondering what they’ll have to retire on or even what they’re going to feed their kids. When wages drop and employment benefits peter out clam diggers are often forced to go out west to seek a better life, a last resort that has little appeal for community-minded fisher folk for whom family, community, and chosen livelihood trump fancy living.

It is an overcast autumn day in Digby, Nova Scotia. Sea breezes sweeten and cool the air. A dense crowd of clam diggers clad in the traditional regalia of Nova Scotian fisher folk–plaid jackets, duckbill hats, jeans, and rubber boots–is milling along the stretch of road between the boarded-up dairy treat building on the right and the bobby-socks era bowling alley on the left.

Environment Canada classifies clam beaches as either closed (prohibiting public clam harvesting due to mild contamination) or open. The federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) has ruled that clams on closed beaches can only be harvested by companies with clam purification facilities known as depuration plants. Clams on open beaches can be harvested for commercial purposes by licensed clam diggers, and you and I and anyone else are legally entitled to dig a limited number of clams for personal consumption; British common law has long ruled that tidal beaches are public, and that any goods that can be harvested from them are common property.

IFP is currently the only company in Southwest Nova with an operating depuration plant, and hence the only body that can issue temporary permits to its employees to dig clams on closed beaches. Existing annual licenses permit IFP not only to harvest clams from open beaches like everyone else but also to be the sole harvester of clams on a prime stretch of closed clam beach at the head of St. Mary’s Bay for the next ten years, or until the beach is declared open, whichever comes first. The company is preparing to submit an application for ten-year leases on 14 more closed clam beaches in Nova Scotia. Environmental pollution will probably bolster IFP’s interests; future beach closures could widen the company’s access to more and more closed beaches.

Stuck in the traffic caused by the crowd of clam diggers is IFP’s Doug Bertram. It is his company’s labour practices and resource management that are being protested. Doug Bertram calls to one of the protesters and asks him to fetch Ken Weir, the president of the Digby Clammers Association. Ken arrives and the two hammer out a resolution; if Ken calls a stop to the protest Doug will raise the price of clams to sixty cents a pound. He’ll also hire back every one of the protesters, with the exception of three men he names. But the clammers association has recently agreed that if one of them has been fired for protesting then they have all been fired. Ken walks away. The protest continues.

Stories in local papers have clouded the issue, to the great frustration of stakeholders in this industry. The suggestion is clear; depuration companies are essential to the continued public consumption of clams. What’s more, It’s implied that the clam diggers are low-class, uneducated people who would sell contaminated clams to the queen if it meant another dollar in their pockets. What isn’t mentioned is the fact that local clam diggers have been volunteering their time to valiant efforts to rescue their resource from being wiped out completely.

Another piece of information missing from news coverage is that depuration companies may not be essential to public safety. Clams are self-cleaning organisms that need only to be left to sit in a clean medium for a matter of days in order to become perfectly safe for human consumption.

One way to accomplish this is through relaying, the practice of removing clams from polluted beaches and moving them to clean beaches in order to facilitate self-purification. A New Brunswick study (Robinson 1991) utilized a number of stock enhancement practices, and found relaying to be a highly effective, low impact, and economical means of decontaminating clams.

Local clammers refer to the process as reseeding, a practice which they undertake voluntarily as part of a community-based management initiative in conjunction with the Clean Annapolis River Project. For the Nova Scotia Fundy region clammers, the purpose of reseeding is to bring up diminishing clam stocks, although it enables purification as well. So far clam diggers have only been permitted to remove the small clams from open beaches for use in reseeding other open beaches; they would like to move clams from clam-dense closed beaches but have so far been denied permission by the DFO.

Doug Bertram sends Ken Weir a court injunction demanding an end to the protest, and threatens to fine him $45,000 a day until the protest ends. He tells the other clam diggers that if they continue their protest they will lose their houses. Fearful that Bertram might follow through, Weir calls for an end to the protest. The three men Bertram has named are dismissed, and clam prices remain too low to provide a decent living for the diggers.

In the fall of 2006 the provincial Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture (NSDFA) and the DFO publicly announced the signing of a joint federal-provincial agreement allowing depuration companies already in possession of one-year clam-harvesting licenses to become eligible for ten-year leases on closed beaches. IFP has only to submit an application and have it accepted in order for the company to control access to 14 beaches in the Fundy region. From where the locals are standing the agreement to grant ten-year leases to companies with depuration plants boils down to a backroom deal with IFP to gradually turn over a public resource to a private company, allowing that company to milk resources dry and then move elsewhere; it is a scenario all too familiar to Maritimers, and this time It’s close to being personal.

Clam diggers and activists have long reported that a fawning DFO conceals IFP’s policies and practices to a degree that justly arouses suspicion, and the licensing agreement looks like a pretty solid indication that they were right all along.

?Innovative’s got such a bad system going now,? says Weir, ?why should the government reward it with ten more years??

News of the impending monopoly quickly galvanizes the very groups who should have been consulted in the first place. An informal coalition comprising clam diggers, clam buyers, municipal councillors, First Nations representatives, and social activists agrees that IFP must not be granted ten-year leases to those 14 beaches. They decide to make public the following demands: ?a transparent and public process which will allow for full disclosure of all data upon which the Federal and Provincial governments? decision is based?; and ?a forum for all affected stakeholders to be heard, before the leases are issued.? The groups decide to call representatives of the DFO, the NSDFA, and Environment Canada to a public meeting in Digby.

Doug Bertram of IFP refuses to allow me to quote him, forbids me to record our telephone conversation, and proceeds to rant for twenty minutes. After Weir’s thorough and detailed analysis of the problems confronting the sustainability of the industry which sustains him, Bertram sounds like a yappy terrier. Weir has told me that Bertram once told a clammer who, after working at a breakneck pace managed to pull in $1,200 in one week, that the man did not deserve such wages because he was uneducated. Judging from my telephone conversation with Bertram, I am no longer inclined to doubt the veracity of Weir’s account.

It is January 31, 2007. The Digby municipal building is swarming with many of the same people who were at the protest. They have brought the same signs. They crowd into the municipal chambers where the meeting is scheduled to take place at 7:00. At a string of desks set up in horseshoe formation, officials from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), the Nova Scotia Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture (NSDFA), and Environment Canada sit at microphones. This meeting is presided over by municipal councillor Linda Gregory, a fisherman’s wife who rules the room with an iron hand. She announces that those wishing to ask questions of the seated officials must first approach the microphone in the centre of the horseshoe and introduce themselves.

The clammers at the back of the council chambers start to grumble. ?We ain’t puttin’ up with it. Naw-sir. They better be tellin? us somethin? er there’s hell to pay.?

Linda holds up a finger and restores order with a sharp ?SSHT!?

The clammers in this room, the communities they reside in, and an international market are all dependent upon an industry whose sustainability is now being threatened by a process of privatization secretly in the works for over a dozen years. Local citizens have had no input into this process because they simply did not know about it.

Part 2 of this article will appear in next week’s Voice.