Since its earliest days the film industry has translated works of literature, fictional and not, to film; everything from fantasies to biographies have been tackled in a variety of ways. What has not been common is the translation of music albums to film.

Since its earliest days the film industry has translated works of literature, fictional and not, to film; everything from fantasies to biographies have been tackled in a variety of ways. What has not been common is the translation of music albums to film.

Until the 1970s, musical films had been mainly Broadway adaptations, yet a transition occurred when popular singers began to appear in films; from Vera Lynn in the 1940s, Elvis in the 1950s, and many others between and since. Undeniably, most such films were thinly veiled attempts to showcase an artist’s music or their singing ability; Elvis being the most overt, using his own songs as movie titles and bases for themes. We now have films such as The Who’s i]Tommy and Quadrophenia, and Pink Floyd’s The Wall, but it was The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine that really broke the mould of earlier musical and film traditions, and started us down the road to bringing artists’ albums to the big screen.

Yellow Submarine is a stunning fusion of multiple animation styles, and it is that variety which is one of its greatest breaks with tradition; the fusion of multiple styles where previously animators had used only one style throughout a piece. As Roger Ebert states “the animation […] isn’t full motion and usually remains within one plane, but there’s nothing stiff or limited about it; it has a freedom of color and invention.” Though it lacks the depth of popular Disney animation, that lack of depth isn’t a flaw, and neither is the variety. The animation of Yellow Submarine, all hand-drawn and overseen by Tom Halley from the designs of the graphic artist Heinz Edelmann, has been described as psychedelic pop and op-art, fusing the styles of Peter Max, Magritte, Escher, Warhol, Vasarely, and more. Yellow Submarine became a vehicle not only for the Beatles’ music (the Beatles themselves had little to do with the movie outside of the music contribution, not even voicing the characters), but also bridged the gap between the different worlds of music, art, and film.

Not only has Yellow Submarine embraced the concepts of intertextuality by borrowing from many different styles of music and art, and “thieving” imagery easily recognisable by its audiences. These images appear throughout the film, but the two main places are in The Pier in Liverpool where Ringo introduces Young Fred to the rest of The Beatles, and in the foothills of the headlands sequence (which includes the song Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds) which connects Nowhereland with The Sea of Holes (or the Holey Sea, which will be amusing to Catholics). These scenes include easily recognisable images and objects such as Magritte’s hat, his pipe, King Kong, Einstein’s famous formula E=mc2, a Union Jack, an American flag, a star of David, a rocking horse, a skull and crossed bones, an umbrella, eyeglasses, various foodstuffs, Marilyn Monroe, a Frankensteinised John Lennon, the names of Sigmund Freud and the Marquis de Sade, and words like never, maybe, yes, no, ah, and ha; all these fuse together in a cultural mish-mash of frenzied rotoscoping that emulates the audiences’ own drowning in cultural icons in the real world.

The film also began to push the boundaries of the usual functional artefacts of the music industry (records, tapes, CD’s, etc.). With the advent of VCRs and DVD players, film can now take its part in the artefact echelon of the music industry. Films such as Yellow Submarine, along with The Beatles’ earlier films (A Hard Day’s Night, Help!), were the grandfathers of what has become the music video industry – whose sole purpose is using visuals to showcase an artist’s music. The variety of visual styles used by that industry is endless, from simple footage of a band on stage, to complex combinations of acting, dancing, storytelling, animation, claymation, computer graphics, and more, each song becoming its own version of a mini-musical.

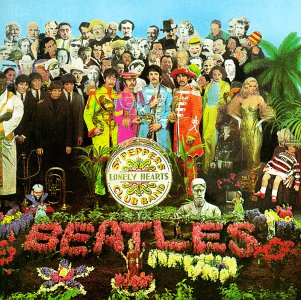

Though traditionalists may not accept it as such, Yellow Submarine is a musical. It uses the cartoonised Beatles to sing and dance through several scenes, and like more traditional Hollywood musicals those musical scenes are connected with dialogue that is used to tell the story. Unlike those musicals, however, the songs seem disconnected from the story and the film itself. The songs may tell us something of the characters – as with Nowhere Man which is used to introduce the character of Jeremy Hilary Boob PhD, the Nowhere Man himself, though Jeremy’s existence in the film does seem like an excuse to use the song, as his function as a member of the cast seems somewhat insignificant – but the story could be told without the songs, though less entertainingly. They seem jammed in, or, rather, the dialogue seems jammed around them, used to connect a concept found originally on The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album. The Lonely Hearts Club Band makes its appearance in the film, as they are saved by The Beatles and then go on, with the Fab Four, to save Pepperland from the Nazi-like Blue Meanies who’ve turned the inhabitants to colourless, soundless, unmoving statues unable to experience joy, or anything at all.

The Lonely Hearts Club Band, the pinnacle of Pepperland music and twins of the animated real-world Beatles, are overtly situated next to a brightly coloured giant YES. This YES, along with the band and all the inhabitants of Pepperland, is crushed or turned blue, and made silent by the Blue Meanies and their minions. Blue-ness is the enemy of happiness, happiness being equated with musical freedom and the colour-rich. Even our animated visit to Liverpool where we first meet up with Ringo, is greyer, flatter, highlighting the drabness of existence, and though hand-painted, uses a cut-and-paste visual style that we would later recognise in the work of Terry Gilliam of Monty Python. The world of fantasy and magic, then, is where one can be most expressive and less rigid than we are in our everyday lives; a world that many think is an offshoot of the drug-induced psychedelia of the era the film was born into.

—————————————————-

This film illustrates battles with demons of various sorts — animated versions of the demons we face in life daily — breaks with traditions of many genres, and adheres to a classic fairytale format with heroes and villains to be overcome. Yellow Submarine combines popular music with orchestral music like more traditional musicals do, and uses animation – something previously left to the entertainment of children – to tell a story to adults. With varying levels of subtlety, it attacks cultural and societal icons, even perverting them in some ways. Yellow Submarine may appear dated and somewhat unreachable due to styles of delivery now surpassed by slicker production and design, and a cultural context that exists in the past, and memories, only, but it still remains an enduringly colourful piece of entertainment that appeals to all age groups.

Lonita has been an AU student since early 2002, and is studying towards a Bachelor of General Studies in Arts & Science. She enjoys writing, creating websites, drinks far too much tea, and lives in hopes of one day owning a plaid Cthulhu doll. The most exciting thing she’s done so far in her lifetime is driven an F2000 racecar, and she’s still trying to figure out how to top that experience. Her personal website can be found at http://www.lonita.net and what you can’t find out about her through that, you can ask her via email: lonita_anne@yahoo.ca