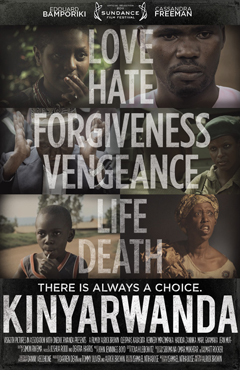

Film: Kinyarwanda (Visigoth Pictures 2011)

Film: Kinyarwanda (Visigoth Pictures 2011)

Writer/Director: Alrick Brown

Cast: Edourd Bamporiki, Cassandra Freeman, Cleophas Kabasiita

Genre: Dramatization based on real events

?Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.?

Martin Luther King, Jr.

?Forgiveness is the final form of love.?

Reinhold Niebuhr

Same Friend, Same High Place, Different Religions, Same Agenda

A group of young menare is gathered at an outdoor classroom, looking like a huddled flock of sheep in matching white t-shirts. Their faces are wounded by sadness; some are on the verge of tears. When they’re asked their names, they appear ashamed to say them.

An attractive young woman addresses them with the steely gaze of a guard dog:

Welcome to the Unity and Reconciliation Re-education Camp.

Forgiveness is not the suppression of anger. Forgiveness is asking for a miracle?the ability to see through someone’s mistakes to the truth that lies within all of our hearts. Forgiveness is not always easy. At times it is more painful than the wound we suffered. Attack thoughts toward others are attack thoughts toward ourselves . . .

So why am I talking to you about forgiveness? You are the ones who committed the crime. You are the ones people have hatred and anger and bitterness toward.

The National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC) of Rwanda was a development of the National Constitution adopted by Rwandans in June of 2003. The idea was gleaned from the Arusha Peace Accord that had been signed there in 1993. Sadly, one year after Arusha, an artful racist propaganda program had persuaded ordinary Rwandan citizens to chop their neighbours to death with machetes.

The radio had convinced many Hutu that the Tutsi were a plague on their country and that true democracy could not be achieved without annihilating them. Hutu were also killed just for being married to Tutsi or for protecting them.

The racist tensions were long-standing, said to have been introduced by Belgian colonists who on first occupying Rwanda measured the physical attributes of the tribes then living there and judged that the Tutsi were more suitable for working in offices and the Hutu were better suited to working in the fields. This racial stereotyping quickly infected the native culture and naturally erupted in chronic inequality and a growing resentment.

At the beginning of the genocide the Mufti of Rwanda, the man responsible for issuing laws and decrees for Muslims, issued a fatwa ordering the slaves of Allah not to take part in the killing of the Tutsi. Many Tutsi, including Tutsi Christians betrayed by their Hutu priests, took refuge in the mosques. In Kinyarwanda we hear six stories based on true accounts of survivors who found protection in the Grand Mosque of Kigali and the madrassa of Nyanza.

The tragedy of the Rwandan genocide was brought to international awareness by the excellent film Hotel Rwanda. What was not made clear in the film was the motivation behind the protagonist’s actions. As a Hutu married to a Tutsi, hotelier Paul Rusesabagina could have stopped at saving his family, but he went on to shelter large numbers of other Tutsi in his hotel.

Perhaps to promote the kind of hero-worship for which Hollywood is so famous, Hotel Rwanda neglects to mention that Paul Rusesabagina was a Christian, a Seventh Day Adventist. He was simply one of the few Christians ready to follow the mandate of his master.

In Kinyarwanda the religious impetus is granted recognition; Muslims and Christians join hands to protect the Tutsi from annihilation. As stated by Symon Hill in The No-Nonsense Guide to Religion, as often as we proclaim the harm done, the fact remains that more good than ill has been done as an outpouring of religious conviction.

Two priceless scenes. In the first, the priest is leading his kneeling flock in the Lord’s Prayer while in another section of the mosque the imam is leading the prostrate Muslims in salat. And in the second, Jeanne, the shy girl from a mixed Hutu-Tutsi marriage, forgives the young man who killed her parents.

Rwanda is a stunning model of what is possible in response to the horrors of human cruelty when perpetuating cycles of fruitless violence isn’t on the agenda.

Kinyarwanda manifests eight of the Mindful Bard’s criteria about for films well worth seeing: 1) it is authentic, original, and delightful; 2) it poses and admirably responds to questions that have a direct bearing on my view of existence; 3) it is about attainment of the true self; 4) it inspires an awareness of the sanctity of creation; 5) it displays an engagement with and compassionate response to suffering; 6) it gives me tools of compassion, enabling me to respond with compassion and efficacy to the suffering around me; 7) it renews my enthusiasm for positive social action; and 8) it makes me appreciate that life is a complex and rare phenomenon, making living a unique opportunity.

Wanda also penned the poems for the artist book They Tell My Tale to Children Now to Help Them to be Good, a collection of meditations on fairy tales, illustrated by artist Susan Malmstrom.